Insights & Commentary

It’s 3’O Clock, stay in brace position

Let’s begin by recapping the equity markets over the past quarter.

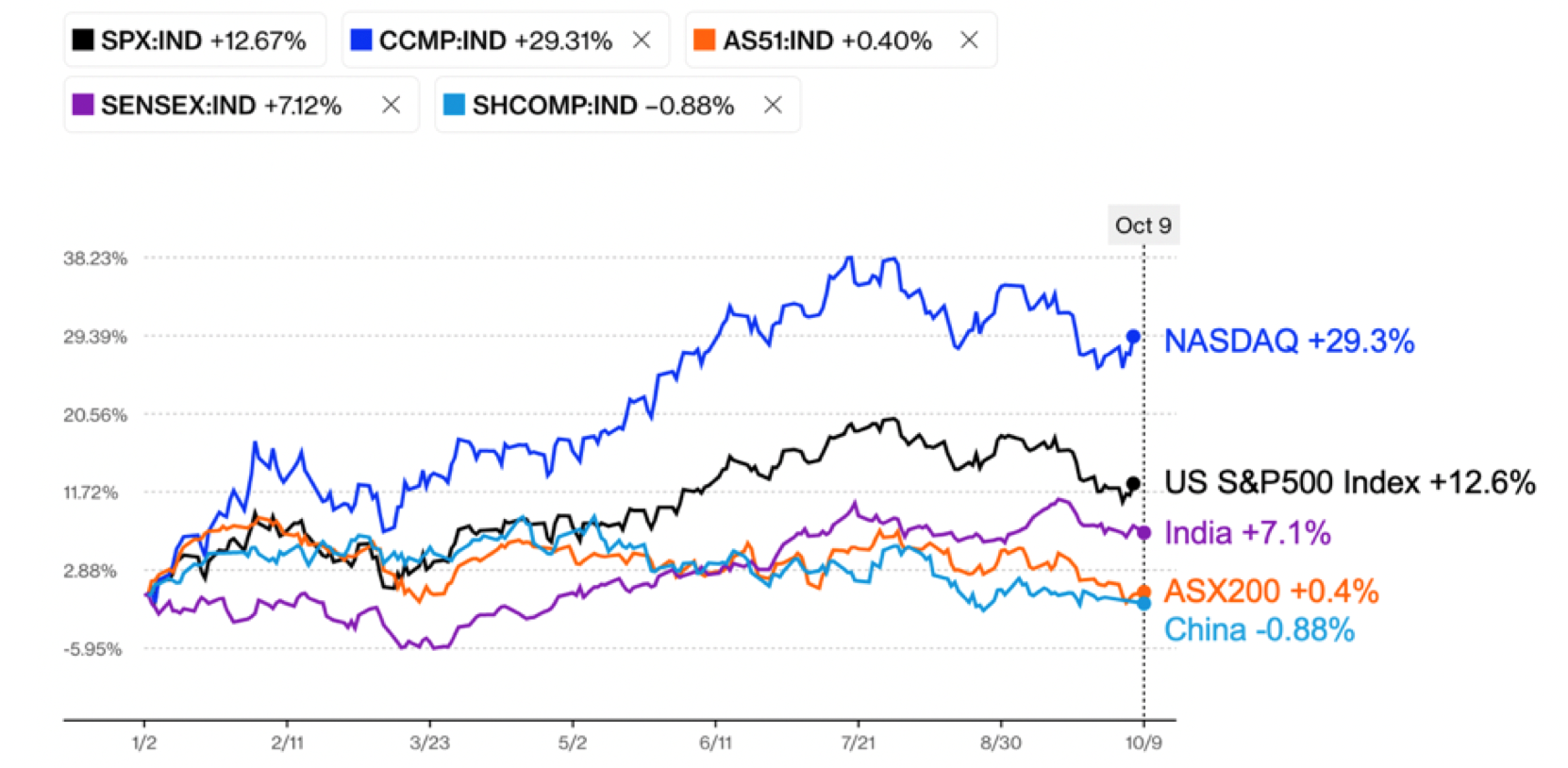

US technology stocks (NASDAQ +29.3%) and, more broadly, the US stock market (S&P500 +12.6%) have consistently outperformed, yielding the highest equity market returns this calendar year to date.

While India takes second spot with a commendable +7.1%, Australian shares barely managed positive returns (ASX +0.4%). Meanwhile, the Chinese share market dipped into negative territory, posting a -0.88% return.

Figure 1: Stock Index Returns Calendar Year to date 2023 (as at 09 October)

Figure 1: Stock Index Returns Calendar Year to date 2023 (as at 09 October)

Over the past quarter, we have taken steps to reduce growth allocations across portfolios. These actions have been timely as we have seen each of the above equity markets (aside from India) record negative returns.

Turning to defensive assets (i.e., bonds & credit), we prudently stayed clear of the government bond market, particularly concerning duration. The havoc wreaked by surging bond yields (i.e., plummeting bond prices resulting in negative returns) would have been detrimental to general investors in the market who had been misguided into government bonds. Both the government bond and corporate credit markets demand caution, especially as interest rates climb due to sustained inflation and rising credit risks.

We continue to emphasise the importance of maintaining high-quality credit (high probability of payment of both coupon and principal upon maturity) and floating rate coupons (short duration). This strategy minimises the risk associated with interest rate fluctuations.

Most client portfolios include investments in the following credit funds, and their performance over the past three months (as of 30 Sep 2023) is as follows:

- Janus Henderson Tactical Income Fund: +1.28% over three months (i.e. 5.12% p.a.)

- Perpetual Diversified Income Fund: +1.74% over three months (i.e. 6.96% p.a.)

- Ardea Real Outcome Bond Fund: +1.54% over three months (i.e. 6.16% p.a.)

The above data is shared to illustrate the following point: reducing growth exposure over the past three months in a weakening equity market and increasing allocations in high-quality, floating-rate credit (while steering clear of government bonds) has proven to be a beneficial approach.

So where to from here you might ask?

It's crucial to note the magnitude of interest rate increases seen over the past year. This has been unparalleled and deserves serious consideration. Historically, similar spikes have invariably led to recessions of varying intensities and corresponding equity market downturns. We neither have the audacity nor the boldness to declare, "this time it's different!" It's prudent to maintain a defensive stance.

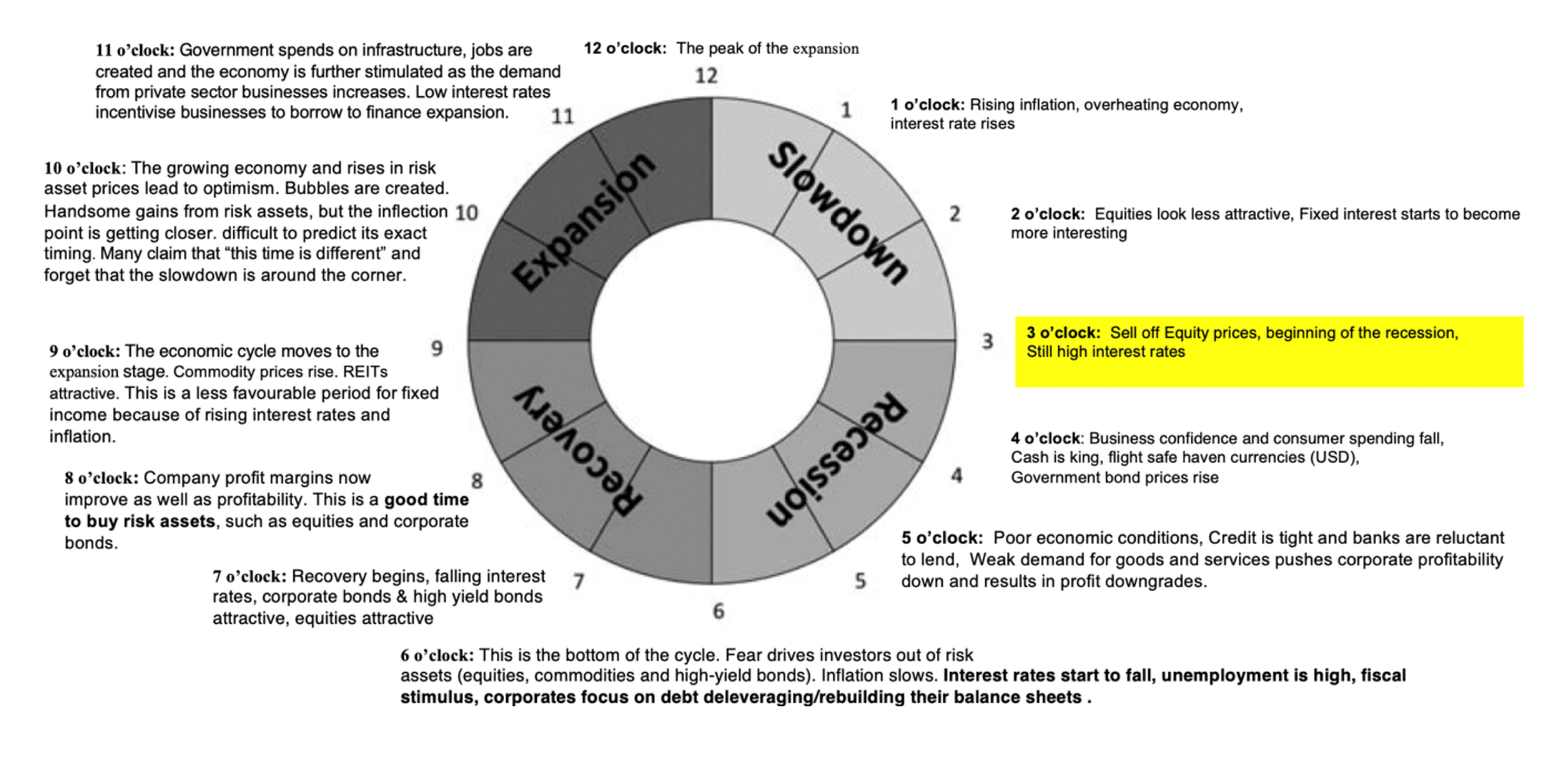

Recessions driven by rising interest rates, often termed "consumer recessions," are typically well-signaled and follow a recognisable pattern or cycle, progressing from peak to trough. A widely accepted method to visualise the economic cycle, including recessions, is the investment clock, first introduced in London’s Evening Standard in 1937. Although the investment clock is a somewhat simplified representation of the economic backdrop, it offers a valuable framework for making investment decisions at various stages of the economic cycle. Currently, we are nearing the 3 o'clock mark, indicating a transition from a slowdown towards a potential recession.

We should maintain a defensive posture to growth until we reach 6 o'clock. A clear sign that we've reached the nadir of this cycle (i.e. 6 O'clock) will be the initiation of interest rate cuts. At that juncture, we may begin to cautiously increase our growth allocations.

Figure 2: Investment Clock

Figure 2: Investment Clock

Is the era of tight credit here to stay?

As we write this, we believe inflation and interest rates (cost of capital) may likely remain high for an extended period.

There are three primary reasons this view:

- The emerging "Cold War 2.0" between the US and China, which is already prompting a costly/inflationary reconfiguration of global trade.

- The disorderly transition to renewable energy, exerting significant pressure on the supply of materials and skilled labour. The oil producing countries (OPEC+) are also likely to harvest the last of the oil revenues by keeping oil & gas prices high throughout the energy transition. All this is inflationary and pushes up interest rates.

- Ageing demographics, which will reduce the supply of capital and labour in the economy. Conversely, this demographic shift will boost demand for goods and services across various sectors to cater to the rapidly ageing population. This will cause interest rates to be higher than the average of the past two decades.

First, there was demographic stability accompanied by high borrowing costs.

From ancient civilisations up to just before the industrial age, the primary age groups - children, young workers, mature workers, and retirees - remained relatively balanced, with little fluctuation. Young workers outnumbered mature workers. The latter typically earned more, saved more, and spent less, whereas young workers were more inclined to borrow and spend. Given the limited number of mature workers, their savings were not sufficient to meet the borrowing demands of the younger population. In other words, with few savers and many spenders, the demand for capital often outstripped supply, leading to consistently high borrowing costs.

Then came industrialisation and urbanisation causing a fall in prices and cost of capital.

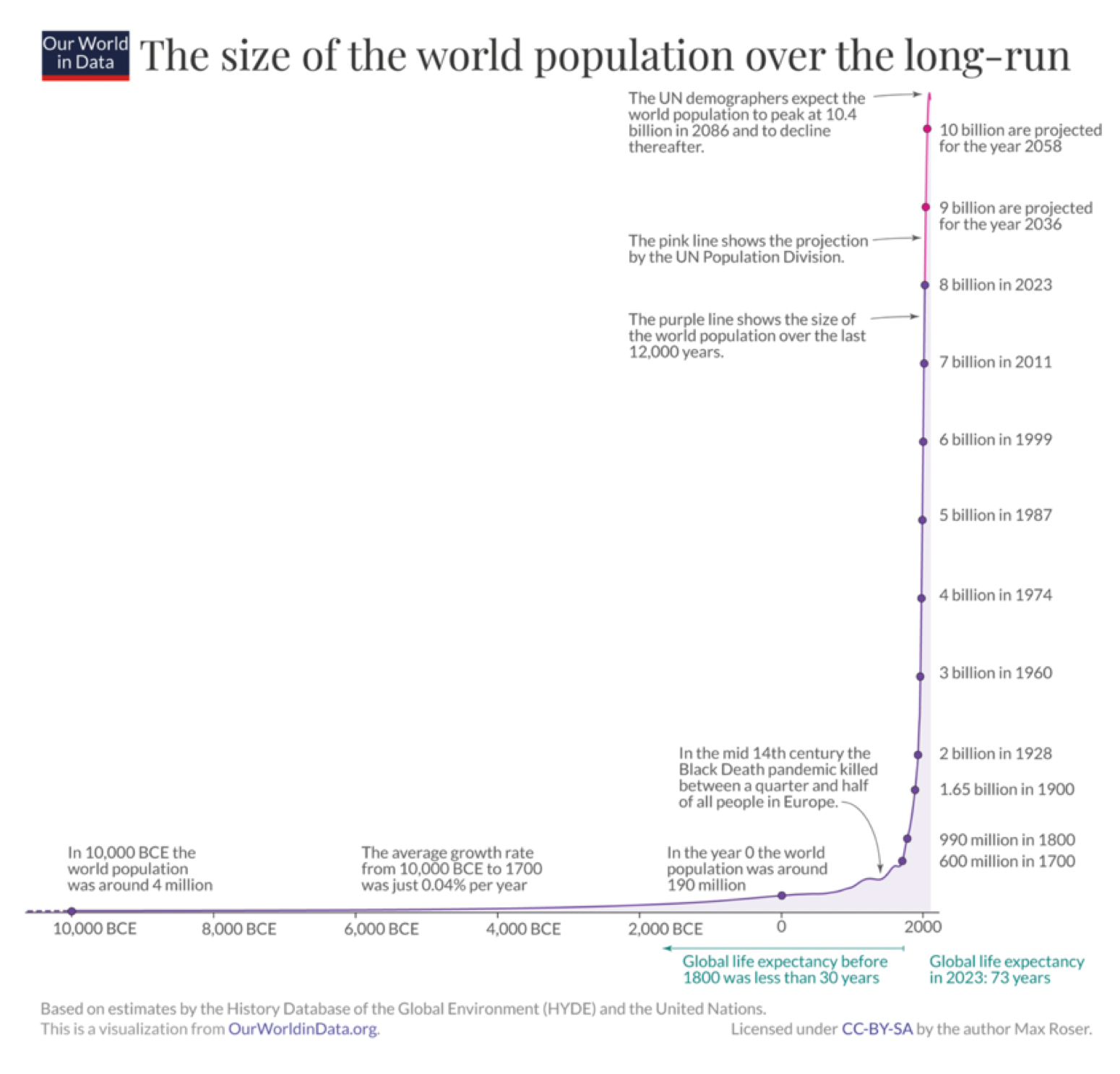

Industrialisation altered the balance between younger and mature workers. With its advent, average lifespans began to extend, and infant mortality rates saw a substantial decrease. This shift led to explosive population growth in nations as they each embarked on their industrialisation journeys. The chart below is particularly illuminating, demonstrating the bulk of this population surge occurred post-industrialisation. Historical demographers estimate that around the year 1800, the global population was approximately 1 billion. This suggests that from 10,000 BCE to 1700, the population growth was rather slow, averaging an annual increase of just 0.04%. However, post-1800, marking the dawn of industrialisation, this dynamic changed dramatically. The global population, which stood at around 1 billion in 1800, has now grown eightfold to approximately 8 billion.

Figure 3: World population explodes during industrialization

Figure 3: World population explodes during industrialization

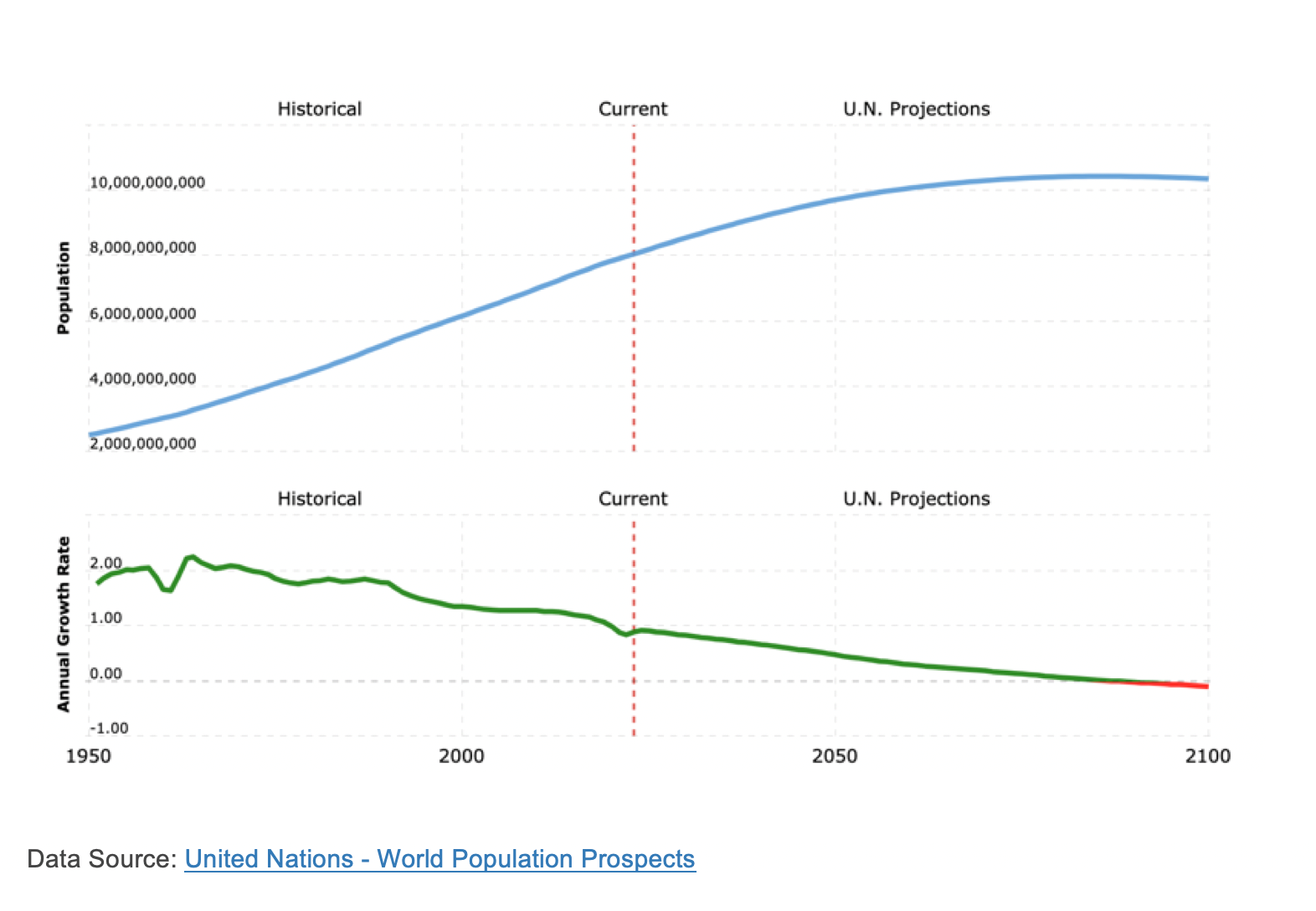

However, there's another trend reversing this population growth, known as urbanisation. Over the past forty years, urbanisation has been gaining momentum, leading populations to gravitate towards urban centers. Accompanying this, education levels have increased, women have entered the workforce in significant numbers, lifestyle preferences have evolved, and birth rates have begun to decline. The chart below predicts global population growth to peak at around 10 billion in the next thirty years. After this peak, the population is expected to decline by the century's end. It's crucial to note that these growth figures, leading up to stagnation, are skewed upwards by developing and under-developed countries. If we exclude the impact of these countries and focus solely on advanced nations, it's evident that their populations have already begun to plateau.

Figure 4: World Population set to stagnate and decline with falling birth rates

Figure 4: World Population set to stagnate and decline with falling birth rates

Let's circle back to the point I made earlier regarding industrialisation, which initially spurred population growth and now appears to be leading to stagnation. Over the past thirty years, particularly in advanced countries like the US, Australia, Europe, and China, an increasing number of young workers have transitioned into the category of mature workers, spanning ages 40 to 60. This cohort of mature workers expanded synchronously across these advanced nations. These individuals, being better educated and employed in specialised, high-skilled jobs, commanded higher salaries. Consequently, they saved more and invested more capital. This dynamic drove up the supply of capital while driving down its cost. The manifestation of this trend was evident as interest rates consistently dropped over the past three decades, reaching an unprecedented low, almost zero, in 2020.

This decline in the cost of capital catalysed a surge in the production of goods and services, ushering us into an era characterised by abundance. Such was the magnitude of this abundance that even unconventional ventures, like cryptocurrencies, received ample funding.

Between 1990 and 2020, a confluence of factors resulted in the most affordable capital and swiftest economic growth ever witnessed in human history. This period was marked by the peculiarities of the fiat age, characterised by extensive money printing. Additionally, the post-Cold War era's hypergrowth, stemming from the stability of global trade and governance institutions under the aegis of a singular superpower, the US, played a crucial role.

Mature workers shift into retirement.

As droves of mature workers retire in this decade and the next, they will shift from saving to consuming their capital. This call on capital will continue as more mature workers pile into retirement and as retirees live longer to fund retirement. So, the diminishing supply of capital from savings will increasingly become obvious. Diminishing supply of capital will thus cause a rise in cost of capital.

We simply don't have a sufficient number of skilled younger workers to replace the retiring mature workers. Looking further down the age spectrum, birth rates are not robust enough to replenish the population mix. Simply put, the influx of younger workers advancing into the mature worker category won't be ample enough to sustain the significant capital supply we've seen in past decades.

This decline in mature workers will also likely lead to governments experiencing reduced tax revenues, as the pool of top tax bracket-paying mature workers dwindles. This demographic shift arrives at a particularly inopportune time. Governments will grapple with escalating costs associated with healthcare, aging, and pensions for the retired workforce.

Concurrently, the private sector will face increased capital demands, especially as it must fund the most significant energy transition in history over the next two decades. Moreover, there's the ongoing challenge of reconfiguring the global industrial base to mitigate geopolitical risks. On top of this, governments in advanced economies face another looming challenge: managing rising interest bills due to heightened interest rates and unprecedented recent spending—a trend that, by all indications, will persist. Given these factors, is it any wonder that government bond yields are skyrocketing?

We have entered a period of opposite trend: a limited supply of capital accompanied by elevated capital costs.

We continue to direct savings into high-quality corporate credit and any investments that consistently yield substantial cash flows for funding dividends and pick growth investments selectively.

As always, remain participated, stay diversified, own quality and invest with intent.