Insights & Commentary

Welcome to the Quarterly Update - March 2025

Markets are correcting - Well that's not entirely true...

This quarter, we've decided to bring forward our quarterly update by a couple of weeks to share our assessment of the current market volatility as it unfolds.

MARKETS ARE CORRECTING

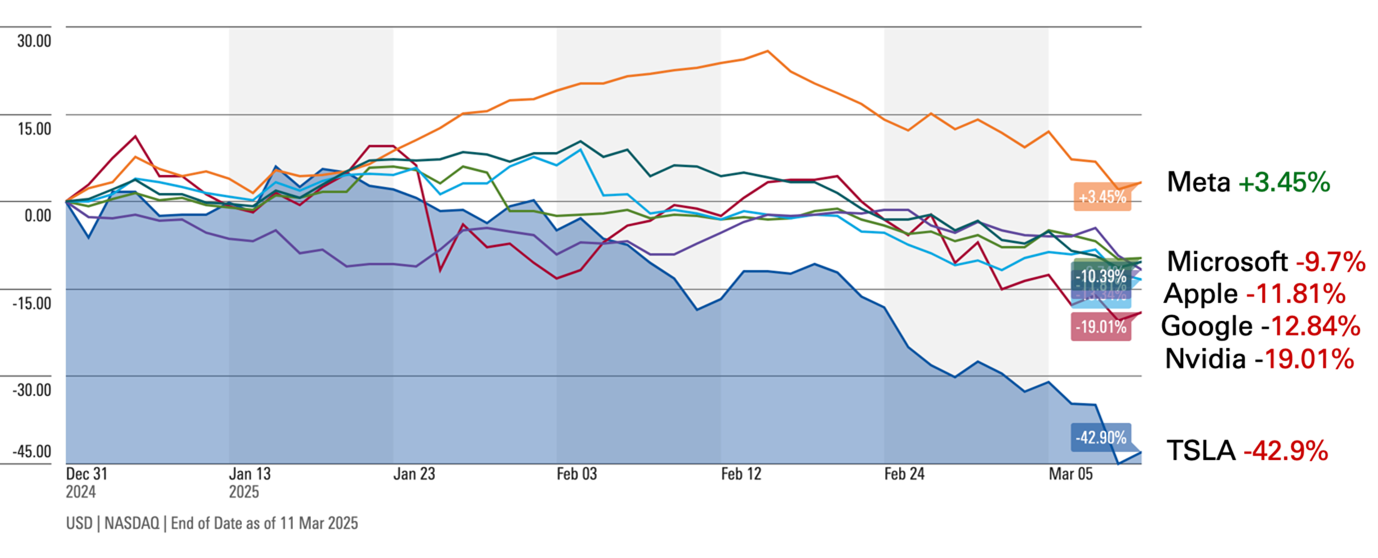

Well, that's not entirely true. However, the largest share market—the US, specifically US technology shares—has indeed experienced selling pressure, declining between 7% and 9% from their peak in December 2024 up to the time of writing this note on 13 March. Australian Shares have also retreated -6.8% from their highs in December 2024.

It's also worth noting that some markets have risen in recent weeks, notably European stocks, the UK's FTSE 100, and global consumer staples. The latter has seen price increases as investors seek refuge in companies that generate dependable cash flow and are less vulnerable to fears of a general economic slowdown.

You may have noticed that, over the past five months, we've been reallocating profits from technology stocks, Australian banks, discretionary retailers, and gold stocks into Healthcare and Consumer Staples sector ETFs.

Figure 1: Global Share Market Returns Since December Peak and 12 Month rolling

Source: Morningstar, Returns as at March 12 Intraday

Source: Morningstar, Returns as at March 12 Intraday

PREPARED, NOT SURPRISED: OUR MOVES BEFORE THE CORRECTION

Below, we share three excerpts from our recent quarterly letters.

In the short term, we believe the Australian and US economies are walking a tightrope, maintaining high interest rates to slow down economic activity and risking a recession...For this reason, we have taken an underweight position in growth for client portfolios

- June Quarter Letter 2024

Trump’s chances of returning to the Oval Office seem to be increasing by the day... expect an acceleration of de-globalization, higher tariffs to protect US industry...trade war against the world, not just China"

- June Quarter Letter 2024

Our asset allocation remains defensive by 5-10% relative to growth...This reflects our response to equity valuations being well above their historical averages... no need to overly tilt portfolios toward growth ... when defensive credit is delivering a respectable 6% p.a. income"

- December Quarter Letter 2024

The excerpts above, along with the market commentary provided in individual client reviews over the past nine months, serve as a comforting reminder that we anticipated this market correction. Accordingly, we've defensively positioned portfolios by taking profits in growth assets, increasing allocations to defensive credit, and enhancing exposure to defensive equity sectors such as global healthcare and global consumer staples.

This market correction was necessary because growth stock prices had advanced so rapidly that a near-term pullback became inevitable. A correction of 15% or more is entirely plausible for broadly diversified indices—and potentially even greater for technology stocks—given the extraordinary pace at which their prices rose.

The two technology stocks that surged the most over the past year were chipmaker Nvidia and EV manufacturer Tesla (which can also be considered a tech stock). Naturally, these stocks experienced the sharpest declines, with Tesla’s share price dropping by 42% and Nvidia’s by 19% over the past two months.

However, it's essential to keep things in perspective. Even after these steep declines, Nvidia and Tesla have still delivered returns of nearly 27% over the past 12 months on a rolling basis.

Figure 2: Year-to-Date Returns of Magnificent Seven Technology Stocks

Source: Morningstar

Source: Morningstar

More broadly, to illustrate how an average Australian investor with the two most common risk profiles (Balanced and Growth) has fared over the past 12 months on a rolling basis, we share the price charts of Vanguard's Balanced ETF and Growth ETF (Figure 3). Returns for both risk profiles have declined since December 2024, affirming that our approach of taking profits was appropriate.

Looking ahead, our goal is to increase investments in growth assets once prices correct and better align with valuations at the broader market, sector, and individual stock levels.

Figure 3: 12 months share price performance of Vanguard Balanced ETF and Vanguard Growth ETF

Source: Morningstar

Source: Morningstar

IS THERE A RECESSION COMING?

Typically, a market correction ranges between 10% and 20%, whereas a bear market—often resulting from a recession—can exceed 20%. The average bear market decline in equity markets is approximately 32%, but such a scenario would generally require the expectation of an imminent recession.

However, it appears unlikely that Australia, the US, or Europe will face a recession (a slowdown, yes). The potential impact of interest rate cuts combined with the money printing capabilities of advanced economies should effectively prevent the worst-case scenario of a deep and prolonged recession.

Indeed, what we've observed from President Trump over the past two months is an active effort to secure commitments—or rather requirements—from global corporations to invest hundreds of billions of dollars into expanding the US industrial capacity to supply domestic consumers. This strategy effectively provides economic stimulus by tactfully leveraging private capital instead of relying solely on government spending.

Similarly, in the past week, the German government—the largest economy in Europe—has dramatically shifted from its traditionally restrained spending philosophy and stringent debt limits. Germany now plans to significantly increase its debt levels, investing €1 trillion in its domestic economy over the coming years to avoid economic stagnation.

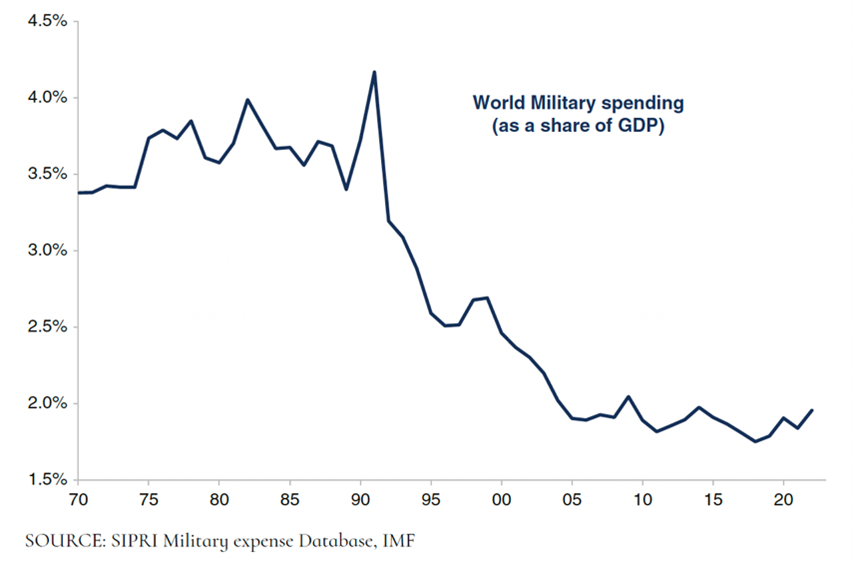

Additionally, global defence spending is on the rise as a direct response to increasing political risks. President Trump’s recent insistence on European countries increasing their own defence budgets underscores a broader global theme of expanded defence funding across major nations.

The chart below illustrates the upward trend in military spending, recovering from the lows seen after the US–Russia Cold War peaks of the 1970s and '80s. With the emergence of another Cold War—this time between the US and China—rearmament budgets are set to rise from under 2% of GDP to approximately 3%, equating to trillions of dollars.

For instance, in 2024, global military spending grew by 7.4% to USD 2.5 trillion—a record growth rate not witnessed since 2009. This trend is expected to persist during the Trump presidency, as countries in Europe, Australia, South Korea, the Philippines, and Japan can no longer assume guaranteed US military backing without increasing their own defence budgets accordingly.

Figure 4: Global spending on defence has trended downwards since the 1970s: World military spending (as a share of GDP). This trend is expected to bump up to 3% range again.

Source: Morningstar

Source: Morningstar

What about the current tariff War between the US and the world? Could this push up inflation and cause economic slow-down?

President Trump came to power with a clear agenda of balancing the US trade relationships with the rest of the world, specifically aiming for a "dollar-for-dollar" match in trade and demanding equal, reciprocal market access for US companies overseas. His primary tool to achieve trade fairness is the use of tariffs. Although the daily torrent of news regarding tariff policy shifts can appear confusing, his overarching goal remains clear. The implementation of tariffs, particularly the 20% tariffs aimed at China—the most significant offender—is proceeding as expected.

For the past three decades, the United States has effectively served as the consumer for global production from various continents. Under the original arrangement established by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, and further reinforced when China joined in 2001, countries agreed to trade largely tariff-free. The expectation was that emerging economies would develop robust domestic consumer markets, benefiting US companies initially by providing cheaper labour, which would boost profits through exports. Over time, it was also expected that these same US companies would profit from selling to the rapidly growing consumer markets within China, India, and Europe. However, the latter expectation largely did not materialize. Instead, domestic corporate champions emerged within these countries, gradually displacing US firms from local markets while simultaneously taking a greater share of exports to the US and globally. This outcome was never going to sit well with the US, and now this issue has been clearly exposed.

Warren Buffett foresaw this scenario twenty years ago in an insightful article published in Fortune (link). Incidentally, Buffett too offered a market-based pricing scheme as a solution for curbing trade deficits with the effect similar to tariffs being used by President Trump. Additionally, Robert Lighthizer, the US trade representative during President Trump's first administration, addresses this topic extensively in his book, ‘No trade is Free’.

No Trade Is Free: Changing Course,

Taking on China, and Helping America’s Workers

Published 2023, Harper Collins

No Trade Is Free: Changing Course,

Taking on China, and Helping America’s Workers

Published 2023, Harper Collins

Both Buffett and Lighthizer present compelling arguments highlighting the urgency of addressing the significant economic distortion created by the US continually borrowing money and selling its assets to finance foreign imports.

Essentially, this arrangement has resulted in a transfer of wealth to foreign nations without reciprocal market access being provided to US companies. The statistics underscore this point clearly: the US now faces a net negative investment position of approximately $18 trillion, meaning foreign entities own $18 trillion more in US assets than Americans own abroad. This imbalance directly results from the US spending $18 trillion more on foreign imports than it earns—a stark transfer of wealth.

One might argue the US actively chose to participate in this uneven trade structure, and while true and notwithstanding the inept WTO dragging out trade disputes for years, it doesn't negate the reality that consistently spending beyond one's means inevitably leads to a relative decline in wealth—so far, placing the US $18 trillion behind other nations. The current administration has chosen to rectify this reckless oversight of the past administrations.

Thus, tariffs are being strategically employed to bring trading partners back to the negotiation table, compelling them to balance trade relationships and offer reciprocal access to US companies. The journey toward balanced trade negotiations has caused considerable emotional reactions so far—reflected clearly in media coverage from countries such as Canada—but ultimately, our assessment is that agreements will be reached, and international trade will normalise.

Reaching these negotiations may cause temporary uncertainty, moderation in economic growth, or persistence in inflation. However, as recent modelling papers from the IMF and RBA suggest, these impacts will eventually smooth out, exerting limited long-term effects on global growth and inflation. We remain well-positioned for the expected short-term market volatility.